Diagnostic Importance of Digital Volumetric Tomography in Detecting a Vestibular Root Perforation: Clinical Case

Машинний переклад

Оригінальна стаття написана мовою ES (посилання для прочитання).

Summary

Achieving endodontic success is associated with accurate diagnosis; establishing a diagnostic hypothesis based solely on periapical radiographs is a challenge for all specialties of dentistry. The complete and dynamic visualization of three-dimensional structures available with digital volumetric computed tomography (DVT) favors a precise definition of the problem and treatment planning.

The objective of this clinical case is to present a real clinical perspective on the need to evaluate anatomical structures in three dimensions, after an endodontic failure associated with a vestibular root perforation of an upper central incisor, which could not be detected from periapical radiographs. The patient was treated in a single appointment, and the perforation was surgically sealed with MTA. After one year of follow-up, the absence of clinical symptoms was confirmed.

In perforations, time is a decisive factor, so the best time to repair the root perforation is immediately after it occurs, thus minimizing the potential for infection at the site of the perforation.

Introduction

The need to evaluate dental structures in three dimensions in endodontic practice has allowed us to diagnose, plan, and resolve increasingly complex cases associated with other technological resources. Conventional radiographs provide two-dimensional images of three-dimensional bodies, being insufficient and limiting in some cases to reveal many determining details and to know elements that have been hidden and/or difficult to appreciate until now.

Endodontic treatment is associated with occasional, undesirable, and unforeseen circumstances that can lead to treatment failure. Accidents during endodontic therapy can be defined as unfortunate events that occur during treatment; some of them due to lack of attention and others being completely unpredictable. Among procedural accidents, root perforations stand out. The greatest complication caused by a perforation is periodontal inflammation and loss of bone attachment. In this sense, their detection, localization, and immediate repair are essential factors for obtaining satisfactory results. On the other hand, this type of accident has been considered the second most common cause of endodontic failure.

Perforations are caused by various reasons, including the difficulty of finding canals due to abnormal morphology, pulp calcification, errors during access to the pulp chamber, during the preparation and shaping of the root canals, in the placement of posts, in retreatments, and also as a result of internal resorption perforating the periradicular tissues.

At the moment the perforation occurs, the supporting tissue (periodontal ligament and alveolar bone) is destroyed, to a greater or lesser extent depending on the size of the instrument used, resulting in an inflammatory process of variable intensity. If the treatment of a perforation is not performed, bacterial contamination occurs, which determines the progression and evolution of the inflammatory process, consequently leading to greater bone destruction in the area of the perforation, and along with it, the adjacent cement and dentin may present areas of resorption.

Therefore, in perforations, time is a crucial factor; the best time to repair the root perforation is immediately after it occurs, to minimize the potential for infection at the site of the perforation.

The repair of perforations can be performed surgically or non-surgically; the clinical procedure will depend on the location of the perforation. The factors that affect the prognosis are: the size of the perforation, the bone and periodontal damage, the time elapsed between the perforation and the repair, the ability to achieve a hermetic seal, and whether the perforation is supraosseous or infraosseous.

This clinical case reports the real importance of TVD in the diagnosis of a vestibular root perforation, its treatment, and surgical sealing with MTA Angelus (Angelus, Londrina, PR, Brazil) in a single session, achieving clinical and radiographic success after one year of evolution.

Clinical Case Description

Female patient, 29 years old, referred to the Endodontics clinic of the General Hospital of the Army of São Paulo (HGeSP). During the anamnesis, she reports intense, pulsating pain and sensitivity in the anterior region, after having undergone endodontic treatment 3 weeks prior.

Clinically, the intraoral examination shows an increase in volume, reddened and edematous, in the mucosa of the periapical region of tooth 1.1. Thermal pulp sensitivity tests are negative, and there is intense pain upon vertical percussion. Periodontal probing was within normal values.

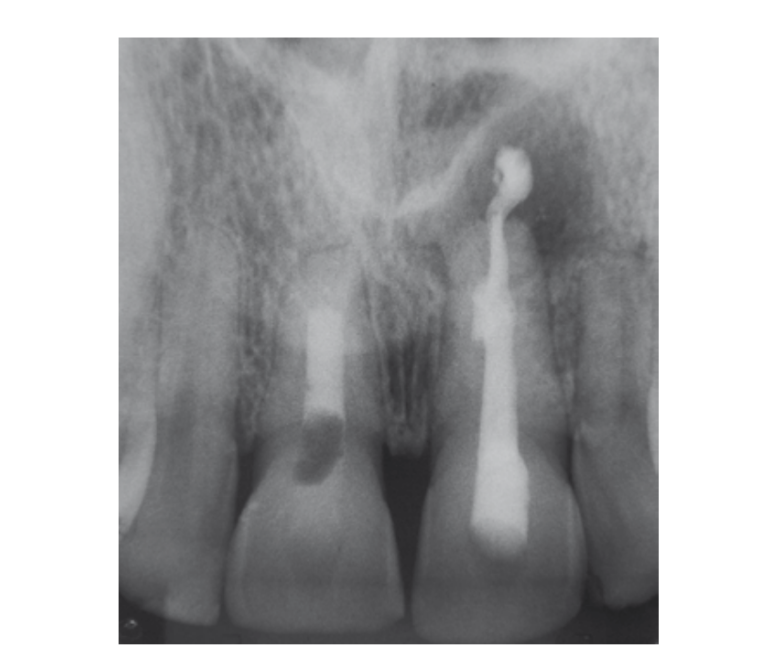

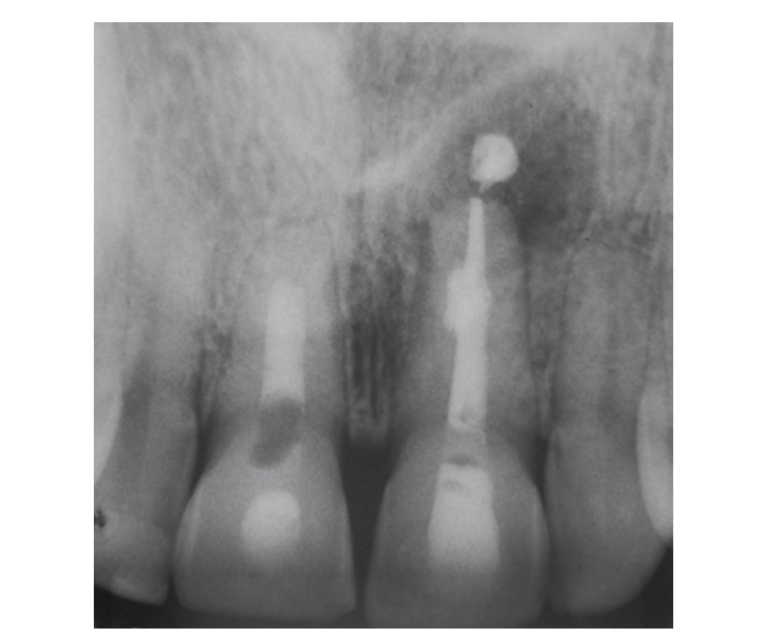

On the retroalveolar radiographic examination (Fig. 1), an endodontic treatment in perfect condition is observed, with no radiolucent areas compatible with periapical or lateral bone lesion or loss. Additionally, tooth 2.1 is evaluated, which has filling material in the periapical region. The clinical findings do not indicate symptoms related to this tooth.

Based on this, it was proposed to perform a digital volumetric tomography.

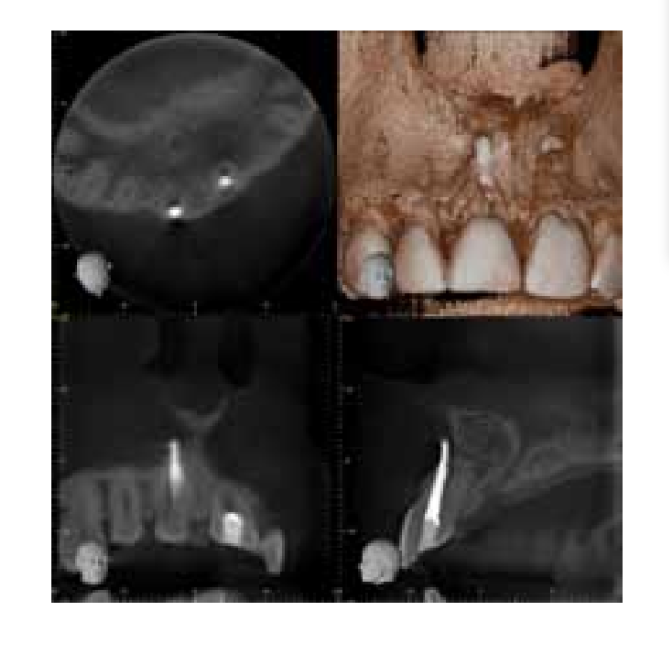

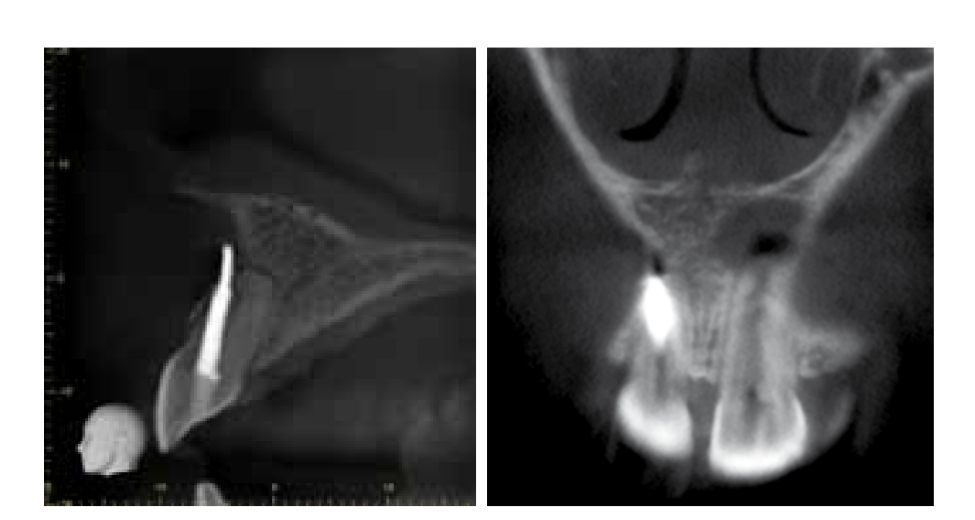

The high-resolution digital computed tomography was evaluated using 3D image visualization software (i-Dixel 2.0 - One Volume Viewer, Accuitomo 80 - J. Morita Mfg. Corp., Kyoto, Japan). In the sagittal and coronal plane view, a perforation with the passage of radiopaque material in the palato-buccal direction compatible with endodontic filling material was observed. Likewise, in the volumetric reconstruction plane, vestibular bone loss and perforation of the vestibular cortex are observed (Fig. 2).

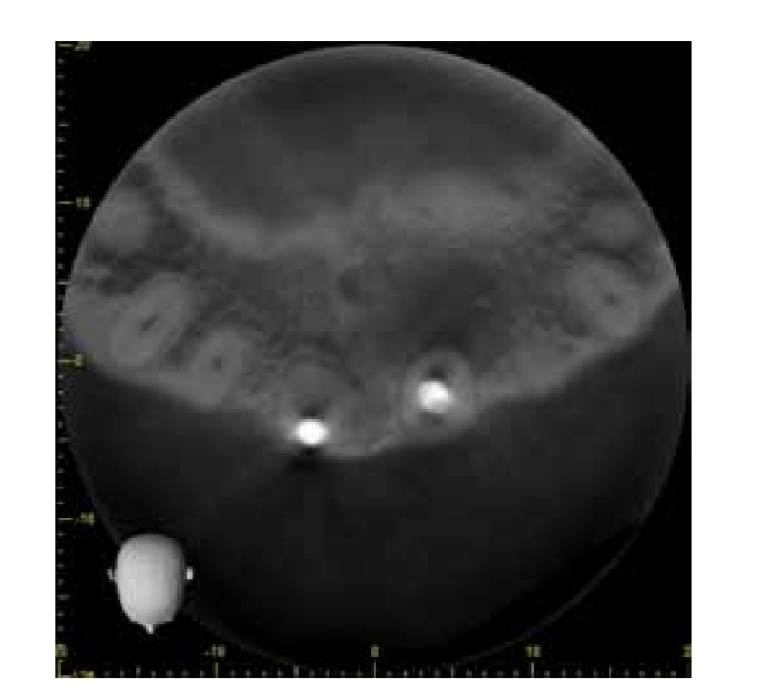

When evaluating the axial plane (Fig. 3), it was possible to observe the loss of centricity of the canal and the absence of visualization of its original lumen, suggesting calcification of the apical third. In the sagittal plane and in the coronal plane, we can observe the exact location of the perforation in the middle third and the deviation of the root canal trajectory towards the buccal side of the filling material (Fig. 4-5).

Based on the high-definition imaging information, the endodontic intervention was carried out. It was established as a treatment plan in a single session, the retreatment via canal and the surgical sealing of the perforation.

After anesthesia and isolation, the endodontic access via canal was initiated, using Gates-Glidden drills (Maillefer / Dentsply, Ballaigues, Switzerland) # 2 and # 3 at low speed for the removal of gutta-percha. The remaining filling material closest to the perforation was removed with Hedström files (Maillefer / Dentsply, Ballaigues, Switzerland) and was profusely irrigated with saline solution. Then, the canal entrance was sealed with temporary filling material.

The periapical surgery began with the asepsis of the operative field, incision, modified Newman flap elevation, osteotomy, and curettage of the perforation area. A profuse irrigation with saline solution was used for cavity preparation, followed by drying. Then, the perforation sealing and reconstruction of the vestibular wall of the canal were performed with mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA Angelus Dental Products, Londrina, Brazil), with the help of manual condensers and wet cotton pellets (Fig. 6). The repositioned flap was sutured with braided silk 3.0.

Finally, a canal filling of MTA was performed, sealing the canal entrance with Glass Ionomer (Ketac Molar Easymix 3M ESPE).

The patient attended a post-operative check-up at 7 days to remove the suture and it was confirmed that during this period he was asymptomatic. In the clinical evaluation, after 12 months, clinical silence was evident, with no painful symptoms, fistula, or vestibular edema, and periodontal probing was within normal values. Radiographically, there was an absence of radiolucent areas or surrounding bone loss.

Discussion

Imaging presents itself as an important tool for reaching an accurate diagnosis based on clinical hypotheses. This allows the professional to establish an appropriate and precise treatment plan. In many cases, perforations are detected through periapical radiographs; however, the use of radiographic evaluation as the sole means for the detection and classification of root perforations constitutes one of the most significant limitations for the clinician. Radiographic detection is often difficult and imprecise, especially when the defect is located on the vestibular or lingual surface of the root. To overcome these limitations, volumetric computed tomography has been used, which provides better visualization of anatomical regions in three dimensions and the presence of pathologies that are often not visualized by conventional radiography. In the present case, it would not have been possible to establish the diagnosis of vestibular perforation without the evaluation of three-dimensional images.

The frequency with which perforations occur and their local damage, both to dental structures and supporting structures, has been a major concern for researchers because they represent an important cause of endodontic failures. In accordance with Fuss and Trope, we believe that the high percentage of iatrogenic root perforations reported in the literature may be reduced in the future, as long as endodontic treatments, especially in cases of curved and narrow root canals or teeth that present unusual root canal systems, are performed by professionals with sufficient prior training.

The prognosis for a perforated tooth depends on: the location of the perforation, the time it allows for contamination, the possibility of sealing it, and the accessibility of the main canal.

Considering the clinical and radiological aspect, the presented case has the peculiarity of having been resolved quickly after three weeks of injury, with an accurate diagnosis and a technique that includes sealing the perforation and placing an MTA barrier simultaneously in a single appointment.

J. Edgar Valdivia, Mário F. de Pasquali Leonardo, Manoel E. de Lima Machado

Bibliography

- Patel S, Dawood A, Pitt Ford T, Whaites E. The potential applications of cone beam computed tomography in the management of endodontic problems. Int Endod J. 2007;40:818-3.

- Estrela C, Bueno MR, Leles CR, Azevedo B, Azevedo JR. Accuracy of cone beam computed tomography and panoramic and periapical radiography for detection of apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2008;34(3):273-9.

- Patel S. New dimensions in endodontic imaging: part 2. Cone beam computed tomography. Int Endod J. 2009; 42(6):463-75.

- Cotton TP, Geisler TM, Holden DT, Schwartz SA, Schindler WG. Endodontic applications of cone-beam volumetric tomography. J Endod.2007;33(9):1121-32.

- Seltzer S, Bender IB, Smith J, Freedman I, Nazimov H. Endodontic failures: an analysis based on clinical, roentgenographic and histologic findings-I. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1967;23:500-16.

- Weiger R, Axmann–Krcmar D, Lost C. Prognosis of conventional root canal treatment reconsidered. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1998;14:1-9.

- Ingle J, Bakland L. Endodontics; Endodontic mishaps: their detection, correction, and prevention. 5th edition, Publisher: McGraw-Hill Interamericana. Mexico City, D.F. 2004: 856-868.

- Sinai IH. Endodontic perforations: their prognosis and treatment. J Am Dent Assoc 1977;95: 90–95.

- Seltzer S, Sinai I, August D. Periodontal effects of root perforations before and during endodontic procedures. J Dent Res 1970;49:332-9.

- Harris WE. A simplified method of treatment for endodontic perforations. J Endod 1976;2:126-34.

- Fuss Z, Trope M. Root perforations: classification and treatment choices based on prognostic factors. Endod Dent Traumatol 1996;12:255- 64.

- Biggs JT, Benenati FW, Sabala CL. Treatment of iatrogenic root perforation with associated osseous lesions. J Endod 1988;14(12): 620-4.

- Tsesis I, Fuss Z. Diagnosis and treatment of accidental root perforations. Endod Topics. 2006;13(1):95-107.

- Lemon, R.R. Nonsurgical repair of perforation defects: internal matrix concept. Dent. Clin. North Am., 1992;36,439-457.

- Roda RS. Root perforation repair: surgical and nonsurgical management. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent 2001;13(6):467–72.

- Castellucci A. Magnification in endodontics: The use of the operating microscope. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent 2003;15:3

/social-network-service/media/default/102339/cc73e2fd.png)